Third year history student MagFhionnghaile lays out some of the facts around the 1916 Easter rising that weren’t mentioned in the songs….

In Short: What was the Easter Rising ?

Ireland, in the first years of the 20thcentury, was a country under direct British rule. The past half-century had seen constant pressure from

Irish nationalists in Parliament to push through the Home Rule bill that would grant Dublin its own parliament, but opposition from the House of Lords and the outbreak of the First World War had, it seemed to many, indefinitely postponed the bill. In the eyes of Ireland’s Republicans, the

nationalists who were prepared to play by Britain’s rules had failed, and action had to be taken.

Over Easter, 1916, the Irish Republican Brotherhood’s Military Council launched an armed uprising in Dublin.

Members of the Irish Volunteers and James Connolly’s Citizen Army occupied strategic locations around the city in a defensive circle around

the General Post Office – the centre of communication for all of Ireland. The British response was sluggish, and at first the only resistance faced by the Volunteers was Dublin’s police and British Army soldiers on leave from the war. Once the Empire adapted, however, the rebellion turned into a panicked rout. A full division of the British Army was deployed, accompanied by a converted warship, the Helga. The ship sailed up the Liffey, bombarding rebel positions and laying waste to the streets surrounding the GPO, while the British infantry encircled the rebels’

defences.

Sheer weight of numbers and the superior weaponry and training of the professional soldiers crushed the Rising, and forced its

leaders to surrender. Sixteen men in all were identified as ringleaders, and were summarily executed for their treason.

Why the need for Rising in 1916 ?

There is no simple answer, nor a short answer, to this question.

To ask why the Irish rebelled is to ask why the Irish rebel, and as major Irish rebellions average out to one every century and a half (give or take) we’d be here all day.

It’s probably something to do with the Brits.

To be brief, the Rising occurred two years after the proposed date of the Home Rule bill, legislation supported by the Irish Parliamentary Party through the 19th century and made into a personal crusade by Liberal Prime Minster, William Gladstone. Despite the best efforts of both parties, the House of Lords united to repeatedly postpone or even outright reject the bill, as most of the peers had land in Ireland they were making money from, and had no interest in altering the status quo. You have to feel for Charles Stewart Parnell, who let his extracurricular activities get between Ireland and Home Rule.

This, by the way, is the reason the House of Lords can no longer reject legislation and can only delay it a number of times. 1914 would have been the definitive date of Home Rule, though the government were still apprehensive.

Not over losing Ireland as direct territory, however.

Opposition to Home Rule was fiercest in what is now Northern Ireland, where the Protestant-majority Ulstermen had no intention of being governed by the southern, Catholic Dublin, and had no faith that a majority southern Dáil would give them the same rights they’d give to their own people.

It’s entirely possible this fear stemmed from the knowledge that if a prominent Ulsterman gained power in the Protestant north, he would immediately use that power to mistreat Catholics. It was, after all, to become “a Protestant state for a Protestant people.”

Regardless of dissident Lords or a hostile Ulster, what eventually prevented the Home Rule bill from ever being enacted was the outbreak of war in Europe. Now, the security of the United Kingdom took precedence over the autonomy of the Irish people, and the bill was delayed again until the cessation of hostilities, which, in fairness to the British government, was not expected to take a long time.

Some things, it seems , have been going on for a while…

But it was felt, among some of the hardliners, that the government had betrayed Ireland for the last time, and the time for politics was over.

Why It Failed

This weekend has been full of celebration.

Parades, roll calls and all manner of militaristic showmanship all celebrating the armed revolution and the forced freedom of a nation. Thousands upon thousands of people flood Dublin and the Air Corps stage a flyover of O’Connell Street. I’d have gone back over myself but I’ll leave it until it quietens down a bit.

. It wouldn’t be too far a leap to say this is the most popular the Rising has ever been.

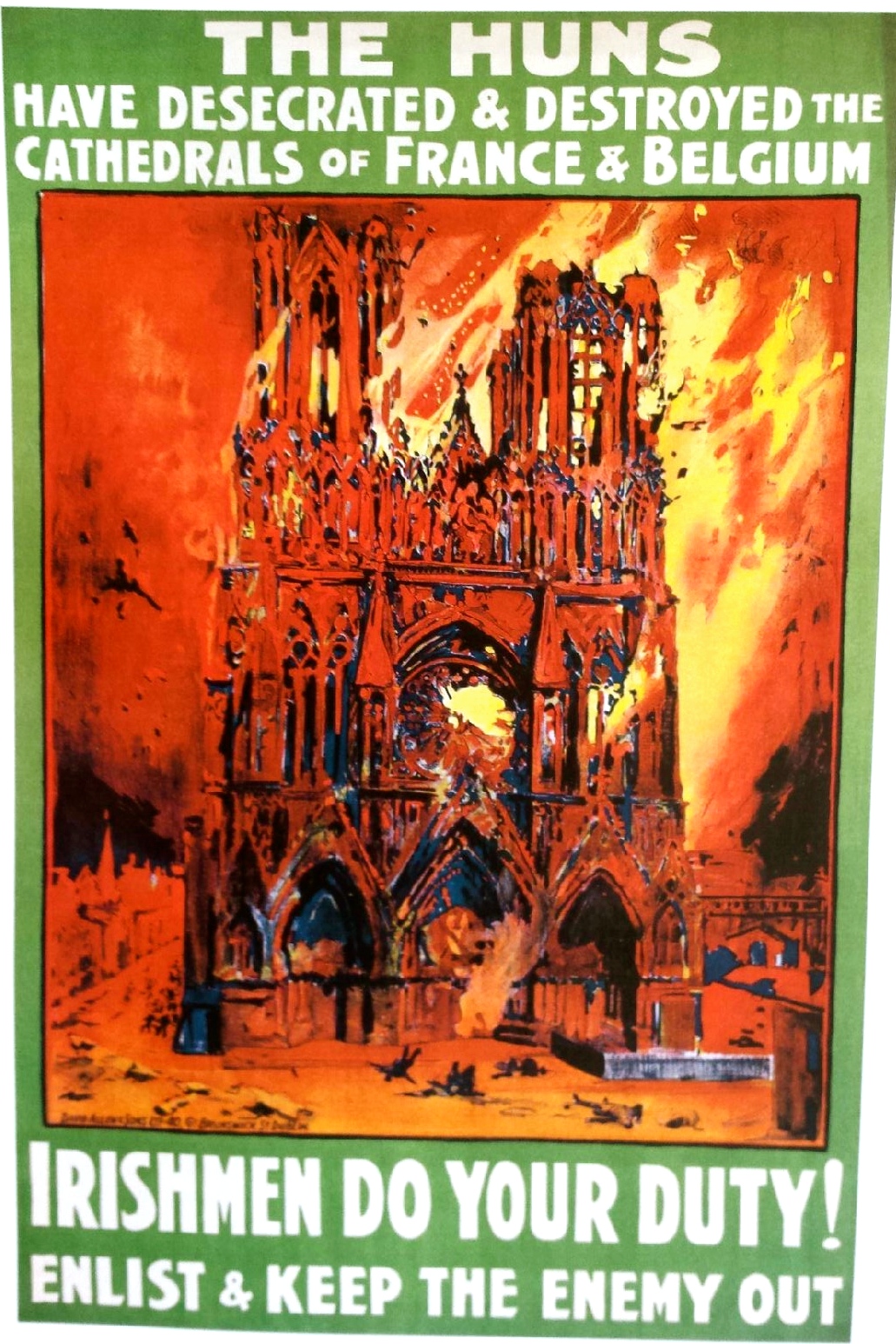

Because it was certainly unpopular when it happened. This picture shows Pearse pinning the declaration to the wall of the GPO building, in front of an enthralled and captivated crowd.

Outside of Irish Times op-eds, it goes mostly unmentioned that the Rising was a result of the machinations of a minority of extremists. Patrick Pearse declared his Proclamation to a bemused public, and Dubliners welcomed the British Army division, sent to crush the rebellion, with applause. This appears strange, from a modern perspective – how can people who have lived for so long under the thumb of the British Empire treat people fighting for their freedom with such derision?

The answer to this is simple. On a personal level, living under the thumb of the British Empire was really no different to living under anybody else’s thumb. The average Dubliner went to work, paid their bills, married and raised children, who would , in turn, go to work, pay bills and raise children, who would, well, you get the picture

Politics was for people with time to waste on that sort of thing.

This is partly why the Irish language was at such a high risk of disappearing.

It was all well and good taking pride in your heritage, culture and language but it wasn’t going to get you a job, was it?

Pearse experienced this apathy first hand in the months before the Rising, as he and a detachment of Volunteers marched on Limerick to rally support for the rebellion. They were chased out by local women, who saw their anti-British behaviour as pro-German, as their husbands had followed the requests of John Redmond and signed up with the British Army. Many of whom would never return.

The Volunteers themselves were another reason for the failure of the revolt. Founded by Eoin MacNeill some years before, they were initially a purely defensive force designed to prevent the British enforcing martial law or any kind of substantial military occupation of the country. They gained more support with the continuation of the First World War, when conscription became a real threat in Ireland.

They swore to resist conscription by any means necessary, unsurprisingly as the birth deaths and marriages columns became heavily weighted on one particular side.

The IRB knew that if they were to have any chance of success, they needed access to the Volunteers’ manpower, and that meant getting MacNeill on side. To this end, they fabricated a document, purportedly from Dublin Castle – the seat of British power in Dublin – in which plans for the arrest of all suspected IRB members, including MacNeill, were outlined. Faced with the threat of imprisonment, MacNeill conceded and gave orders to the Volunteers all over Ireland to march. The national revolution seemed inevitable, until Maundy Thursday – or ‘the day everything went wrong.’

With the help of Sir Roger Casement, a British official with connections in Germany, the IRB secured 20,000 to 25,000 Mosin-Nagant rifles, ten Maxim machine-guns and vast quantities of ammunition to be transported aboard the Aud, a German ship disguised as a Norwegian ship from Lübeck to Tralee Bay. The vessel was due to arrive on Maundy Thursday, but circumstances changed and the IRB altered the plan. As the Aud lacked a radio, the captain was not informed and the ship arrived in Tralee Bay on the original planned date. Once there, it was ambushed by HMS Bluebell, which was already looking for it, and the cunning use of a Norwegian flag didn’t really fool them. En route to Cork Harbour, the captain gave the order to scuttle the boat and send the guns to the seabed, keeping them out of British hands, but leaving the Volunteers woefully under-equipped.

The misfortune of Maundy Thursday continued – as one of the cars sent to meet the Aud crashed en route, killing all of its occupants.

Without the guns and ammunition, MacNeill realised the rebellion was doomed. To make matters worse for the IRB, he had also discovered the Castle document was a forgery, and he quickly ordered the Volunteers nationwide to stand down. A national revolt was to be constrained to a Dublin revolt – one whose opening shots would be aimed at Irishmen in British uniforms. Men who were either trying to earn a living for their families, or who were fighting for their country which, at the time, was Britain.

It remains extremely important to remember that nobody in Ireland in 1916 knew of an Ireland outside of British rule, and that for the majority of Dubliners there was no significant reason for considering the two landmasses as separate entities.

History cannot be fully understood unless we look at it through the eyes of those involved.

And How It Succeeded…

Despite the glaring failures, needless deaths and lack of strategic foresight, the Easter Rising was a resounding success.

It may not have been the success the IRB expected, nor the success they were aiming for, but they succeeded in provoking the British Empire. As the leaders of the Rising were pushed into the spotlight and in front of a firing squad – made up of the same Sherwood Foresters who were ambushed at Mount Street Bridge, with the loss of around two hundred lives, as they had decided that the tactic of walking slowly toward the enemy had not worked in the trenches, it might work in the streets… the British and Irish public saw them for who they were.

An idealistic poet, Patrick Pearse, was given the same treatment one would expect to be reserved for one of the Kaiser’s men. James Connolly, who was too injured to stand, was shot in his wheelchair. The elderly Tom Clarke was stripped, humiliated and tortured before his execution.

Thanks to the British government, the IRB no longer appeared as an armed, extremist group of traitors, and instead took on much more sympathetic images. While the anger of the British can be explained by the ongoing Great War, and the solicitation of German aid by the IRB, it simply cannot be justified. The Volunteers who survived the Rising in Dublin, and those who stood down elsewhere in the country, still held their Republican ideals, and they now had a total of sixteen martyrs for their cause.

The British government knew this, and they responded accordingly. Dissidence was met with the iron fist, which, naturally, only provoked further resistance. A game of escalation was played, as insurgents struck at bolder targets, and British security forces reacted with more and more aggression, eventually culminating in what would be known as the Anglo-Irish War, or, to the Irish: The War of Independence.

Ralph adds

Elsewhere in the world, other peoples under colonial rule sought out and found inspiration in the Irish, and whilst the British have still to let fully go their closest colony, others were to have more success.

The leaders of the rebellion will be remembered for their part in encouraging the Irish to seek freedom, but it could also argued, and argued well, that they provided inspiration that was ultimately to lead to the eventual break up of the Empire.

And that’s no bad thing to be remembered for.

Good read that.

There is book just published by Ruth DudleybEdwards whinproporyd to be an historian that examines dome if the key players in the Rising.I read her comments on the book but not it. She quibbled with the Proclamation’s claim the Rishmen had exercised their right to freedom in “every generation.” As the author of this article points out that wasn’t strictly accurate but since Stronbow’s invasion in 11.70 the Irish had fought the foreign oppressor pretty nearly every century. In 1870.1848, 1798 and from the resistance to Cromwell to the broken Treaty Stone the Irish assertion of Independence was firm and frequent. Dudley Edwards thesis to honour the men (and the women) of the Rising as the cause of IRA violence in the 70s and 80s, shows a dangerous ignorance of other Irish martyrs.

A more careful analysis might have looked at the British politicians and media who ignored the serious injustices in “Ulster” (or part of it) from 1921 until 1968, a better culprit for the violence. Ironically current Sinn Fein have probably more in common with Collins and the “Free Staters” than the 1916 martyrs, with the exception of the Hunger Strikers of course. They have opted for a pragmatic approach and an end to violence which is understandable but the issue of Irish Independence has been parked not resolved.

sobering truth, now let us know about the “famine”, ????? no such thing , blight was all over Europe read wiki – pedia.

Rangers died.

AMEN!!!!

The SPFL SFA UEFA ASA ECA Lords Nimmo Smith and Glennie etc etc disagree wiyh you. And it’s their views that count. Amen.

The ASA???? What, those bastions and guideline makers of world football? Show us all where UEFA and the ECA have stated that you are the same club with history (but not debt) intact? Silly zombie.

“read wiki- pedia” ,

so that’s your source for history, fuck me !

Try some real historic research you lazy bastard.

England’s blame was never claimed to be the blight itself; their blame was in their reaction to it , or lack of , to be more precise .

flak…..get your jacket.

On fire the day andybhoy 😉

God bless the hero’s of 16

Tiocfaidh ar la

All over Europe, oh well that’s all right then, the million who died will be quite relieved.!

Any thoughts about Ernest o mallaly?

(getin old )

An army whithhout banners?

am i dreaming that i read this book?

Ernie O’Malley was an officer in the Irish Volunteers who organised battalions and companies around Ireland after 1916.He eventually became O.C. of the second southern division of the IRA during the tan war.

His first and most famous book is, On Another Man’s Wound (published in the USA as Army Without Banners). This book has been described by many as the best account of the fight against British rule in Ireland from the republican side.

His next book The Singing Flame deals with the Civil War and his subsequent imprisonment.He was the last republican released by the Free State government in 1924.

I think these books should be read by any one interested in that period of Irish history.

Check them out,not just history great reading.

or am i confused with the riddle of the sands?

Just generally confused I think…..

k

are you thinking of Erskine Childers!

BJF,

I think it is trying to think…..

K? After me, pay attention…

ABCDEFGHIJK….:)

Alpha

Bravo

Charlie

Delta

Echo

Foxtrot

Golf

Hotel

India

Julie

Kilo

STOP

He’s referring to “An Army Without Banners: Adventures of an Irish Volunteer” by IRA man Ernie O’Malley.

God bless e o malley and Erskine childers

letters from Erskine to his wife truly heartbreaking, that is what you call guts.

E O Malley with caps

1916 was of coarse the catalyst for the move to Free-State and eventual Republic , but it’s important to remember that it took Collins pragmatic military approach (guerilla warfare), after the 1916 Rising, to bring this about.

Well done for being a 3rd year student, some advice from someone who has studied Irish wars for 40 plus years

1. you should always think for yourself and never accept a written account without cross reference and by using basic logic of how humanity works and always doubting any British military official account!

Before you make a claim be sure it is likely if not proven, because the small assumptions or naive claims can destroy a overall thought or claim.

such as when you state –

” This picture shows Pearse pinning the declaration to the wall of the GPO building, in front of an enthralled and captivated crowd.”

Did you know that picture is actually from a 1966 commemoration Calendar! that besides! perhaps you might want to reconsider your conclusion!

on your credible reflection it’s unlikely you will have many agree the artist is suggesting a crowd let alone a enthralled and captivated crowd!

I have not read all because some of your claims are naïve and misleading points halt progress! and therefore you do your overall efforts a injustice

for example.

“Sheer weight of numbers and the superior weaponry and training of the professional soldiers crushed the Rising, and forced its leaders to surrender”

Whilst you actually contradict your own (professional) point later, but to add

1. By their own account and using logic! it is clear the Leaders of 1916 never seriously imagined a short term victory in any pure military sense!

(even with the Aud guns and a hundred times more Auds)

they set out to last long enough for world attention! which they clearly achieved.

they set out to inspire!

Clear also they only surrendered because of British indiscriminate use of artillery pieces and Helga gunboat guns, the British disregard for civilian casualties is what persuaded Pearse to offer a surrender.

Just before surrender Pearse mentioned his notice of the bodies of 3 old men civilians laying dead in the street who had been shot by the British, was the push to cease.

We know the Leaders did not anticipate the British shelling Dublin indiscriminately – as Connolly (former British soldier) had assured Pearse they would never shell Dublin as they were lose too much money in their surrounding financial assets.

Connolly not being born in Ireland possibly confused how the British might likely react if the rising took place in Britain, where they have proven to have double standards!

extremely violent Miners strikes – but not a shot fired

same with Brixton riots

same with recent London summer riots

where as in Ireland the British shoot first! Bloody sunday murder of innocents and peaceful protestors, is actually only one of numerous examples of British extremes of violent response reserved for the Irish and other former colonies.

In Britain you call it a Police station in Ireland it is a barracks!

Don’t kid yourself that most Irish did not see Ireland as one and Britain as foreign and still do!

similar but as foreign as Canada or France or Australia.

2. it is recorded some if not most of the other leaders wanted to fight to the death.

3. the leaders (especially) knew they were not going to win! they knew they were going to die or be made a example of, Clarke and Pearse and Connolly and McBride all knew they would either die fighting or be executed, it was a fundamental part of reasoning for the rising.

It was to be a stand for the soul of Ireland

they knew how Westminster would react, they were depending on it! – they were convinced (and proved correct) the British political reaction (executions, martial law, wide scale arrests and abuses) would enrage many otherwise indifferent Irish and convince a nation.

Of course the empire would defeat the initial Irish rising, the Irish had few weapons.

But your idea on “professional British soldiers!!

A blanket and naïve statement to put it mildly (to be fair that general naivety on the general quality of british military recruits is equally naive today)

It is known for example the Sherwood foresters were raw, some had never fired a gun before.

around 200 were killed and injured in the first couple of days.

on the 26 and 27 April in Mount Street and the South Dublin Union

around 1200 British soldiers of 178th (2/1st Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire) Brigade, an infantry brigade of the British Army were fighting around 100 Irish (just 2 Irish snipers held 300 at bay and who retreated) and the Irish suffered only 4 dead and around 20 injured!

ironically when that reality is known – that hand to hand, man to man the British were taking a hiding and extremely high pro rata casualties – it helps explain (if not justify) why the British Officers ordered a halt to all frontal Assaults and reverted to shelling of enemy positions from a safe distance, and paid little caution concern to civilians they might and did kill.

Back to your conclusion of

“It remains extremely important to remember that nobody in Ireland in 1916 knew of an Ireland outside of British rule, and that for the majority of Dubliners there was no significant reason for considering the two landmasses as separate entities.”

A Nonsense conclusion I would say, a conclusion assumed because of british bias and dominance of past records

and a nonsense conclusion assumed from 21st mindeset!

Did you know for example

in 1798 (equivalent for someone today recalling WW1) that more Irish died fighting for freedom against Britain than Americans did in Vietnam or French in their revolution

that at least a million had died of hunger because of imposed economics of a foreign colonial power in the 1840’s. and several million would be forced to emigrate (equivalent for someone today recalling WW2)

Irish knew and remembered!

the Irish in the British army in WW1 were also often Irish Volunteers!

of a close to 200,000 strong Irish volunteer force who signed up for this militia who’s primary reason to exist was to if necessary) force through home rule ( independence in all but name for that time)

Read up on The Connaught Rangers Mutiny in India – 1916 Rebellion

there was widespread discontent in the Irish in the British army when they read of the reaction to ‘their countrymen’

Self explanatory!

Did you know a similar staggering number of sworn Fenians were inside the British army of the 19th Century

the Irish made up a high % of the British army and navy for centuries.

before the Fenians existed – read about Navy Mutinies at Spithead.

and on a civilian level!

Paramatta in Colonial Australia

the Irish clearly did consider themselves different in 1916 and had for centuries and still do despite similarities.

we are after all American Lite today!

Just because people take jobs does not mean they want to.

We can witness what happens to abused and broken people all over the world

Just because Iraqis line up for military and police jobs in a ‘new Iraq’ does not mean their mindset has changed one iota.

the Irish were fighting for all sides for centuries (much like any landmass of people including english and scottish to native american)

Irish were fighting for reward or hire for Vikings for Normans even in latter stages in Cromwells army!

Does not mean squat!

that some women came out to complain in Dublin 1916 was natural as they were concerned for their husbands abroad and because

in no small way because their access to weekly benefit had been put on hold because of martial law.

most were desperately poor!

the Irish did consider themselves as different, even when the Irish language went into decline.

Your advice is rather poor and very one-sided. Why would I doubt only British military records? I doubt everything I read, and that’s why I read so much of it. I also tend to consider things beyond face value – for example, the image I used of Pearse outside the GPO clearly depicts no enthralled crowd, though my caption states the opposite. A little application of logic would’ve helped you work out that the caption was sarcastic. Did you notice it also went against the point of the article? Or was that one of the parts you didn’t read?

Nevertheless, I stand by that point. You can argue that the Irish people considered themselves alone and separate to the British for the entire modern period, but there is more evidence to the contrary than for it. The crowds that turned out to greet the British monarch at Dún Laoghaire and Ballsbridge on the famous route to Dublin – and the popularity of that royal family in the Irish press is covered very extensively in Mary Kenny’s ‘Crown and Shamrock: Love and Hate Between Ireland and the British Monarchy.’ Of course, you might argue that the Irish press was controlled by the British, and you would be right, but that simply does not account for the rise in sales of newspapers featuring stories about the British monarchy during ‘important’ (if you consider royal celebrities important) events.

Your use of the Famine as an example of the separation of nations is also an interesting claim. As a result of the Famine, most Irish people had relatives living in England, Scotland and Wales, meaning that there were actual blood ties between the nations. Travelling between the two for family events and even for work was common. Your references to 1798 and to some sense of strong, Gaelic nationality would make more sense if we were discussing a national rebellion, but the simple fact of the matter is that we are talking about Dublin. We are talking about the Pale. The links to 1798 would be stronger felt in the West, especially as I strongly doubt children learning about 1798 and the Famine in Dublin schools were being instructed to rise against their British masters, given that they were being educated in the centre of British influence.

I would also like to add that your references to post-1916 mutinies or rebellions by Irish people elsewhere in the world are entirely irrelevant to this discussion, given that I quite clearly stated ‘1916 changed everything.’ Which you would know, had you read the article, which, by your own admission, you have not.

But now I’m going to discuss your ‘jobs’ comment. It’s quite a bold claim to make that Dubliners were more preoccupied with getting Independence than earning a living, and since you’ve provided no evidence, I’ll provide some to the contrary. Take a look at employment and emigration from 1937 onward. I don’t need to tell you that 1937 marks the ‘official’ beginning of Éire as an independent nation, but I probably do need to point out (or you can look for yourself, I find ‘Personal Narratives of Irish and Scottish Migration, 1921-65’ by Angela McCarthy to be a perfectly useful source) that emigration from Ireland to the UK surged after that date. A letter from one such emigrant worker (featured in Crown & Shamrock) outright blames “de Valera’s Republic” for the sudden shortage in work. There’s a sad irony in the fact that Dev and the others fought so hard for Irish independence, and then caused so many of their citizens to go to England just to earn a living.

I take serious issue with the end of your comment because you’re implying that one Irish person’s opinion means more than another. You imply that the ‘Dublin women’ (it was actually Limerick women in the Pearse incident) objected to the Volunteers because they were receiving money from the Brits. Rather than asking why the Volunteers made no provision for the people they’re supposedly fighting for, you take this as cause to dismiss their opinion. You also say they fought for the Normans, which is sort of true. MacMurrough allied with Richard de Clare, or Strongbow, and it was mostly using the crown of Leinster that they were able to rally the support of the Gaelic people. It’s unlikely Strongbow would have enjoyed as much support as he did, had he not arrived on Ireland’s shores three years after MacMurrough, exiled King of Leinster, had seized Wexford and already prepared for the arrival of the Anglo-Norman forces.

But now I’ll discuss your summary of British military tactics. You are correct in saying that the British forces were, by and large, raw recruits who’d never fired their guns before. This is true. You are incorrect, however, by denying that they were trained. The British Army were more co-ordinated than the Volunteers, who struggled to communicate between strongholds. James A. McKay’s biography of Michael Collins covers this quite neatly. Military training is not simply fitness and firearms.

As for heavy casualties and close-quarters fighting – the only major incident that can be described as a loss for the BA is the ambush on Northumberland Road and Mount Street Bridge. There were a few reasons this ambush was such a success for the Volunteers. Enclosed streets caused the sound of the shots to echo, making the location of the Volunteer snipers impossible to trace. This, in turn, made taking cover almost impossible for the British soldiers, who were inexperienced and relatively easily panicked.

I do have to point out that the term ‘professional’ just means ‘gets paid.’

Finally, because this is going on a bit – let’s talk about the leaders’ suicidal ambition.

You’re familiar with Eoin MacNeill, I presume? MacNeill was a man who had no intention of dying for Ireland. This is why he refused to raise his Volunteers to action until the IRB forged the Castle document to persuade him of his impending arrest. It was his intention to secure Home Rule for Ireland, by force if necessary. It was never his intention to become a martyr, and while the poet Pearse may have held the romantic ideal of a ‘blood sacrifice’ in his head going into the Rising, the same cannot be said for certain of the other leaders. It certainly can’t be said for the Volunteers beneath them. De Valera was in no hurry to correct the British government when they granted him clemency based on his American background (though I do have proof of a letter stating his American background isn’t what saved him: though the Senator who wrote it also called him ‘Edward de Valera’ so make of that what you will) and neither was Michael Collins, or Cathal Brugha, or any of the other men who avoided execution. Try not to mix up the acceptance of fate with a deliberate sacrifice.

And finally, I’m just gonna quote you right here:

“the Irish were fighting for all sides for centuries (much like any landmass of people including english and scottish to native american)

Irish were fighting for reward or hire for Vikings for Normans even in latter stages in Cromwells army!

Does not mean squat!”

So, I will ask you a question. I’ll critique your work.

If it doesn’t mean ‘squat’ that the Irish fought for Vikings, Normans and Cromwell, why does it mean anything more that they fought for the IRB? Is this not evidence of the disparity of ideology in Ireland? Is it not an argument against generalisations or romanticisation of nationalist causes?

Double standards, mate.

Interesting stuff I’m sure mate but you have to remember the Author of the piece has a disclaimer on every Diary that states he has the right to:

A Talk as much shite as he wants

B Make up stuff off the cuff for comedic effect

c Is normally out his box on Kestrel by the time he writes it

It’s not intended to be factually spot on bud ,more a comedic slant on the given subject of the day.

Chill oot ffs.

HH

I’m not the author.

Charlie, I think you should re-read this. It is intended ” to be factually spot on” in Magfhionnghaile’s article. And to that degree it fails.

Ralph only wrote the add on at the end. IMHO Magfhionngaile made a good effort, but Patjo’s observations are valid and well reasoned.

As regards ruth dud edwards, she is a west brit who wouldn’t acknowledge/recognise that an Irish martyr ever existed, so I agree with Seosamhgailt.

Good effort though Magfhionnghaile

Brencelt

The reply from Magfhionngaile is worth a read. Nice to see debate on soemthing that isn’t Ronny Out.

I was under the impression facts were a big no no in here?

FACTS OUT! 😉

YOU Ruth Dudley Edwards bastard child that’s not allowed out her British dungeon your full of bull(dog)shit “shame theyve sold there own mother”padraic Pearse mise eire