There is a moment that arrives in every dominant club’s lifecycle when comfort becomes complacency, when the applause for domestic success drowns out the alarms sounding from abroad. It should be familiar if you’re a Celtic fan; that moment has lasted two decades.

.png)

APATHY: DOMESTIC DOMINANCE, EUROPEAN IRRELEVANCE

Numbers tell one story. Since the 2005-06 season, Celtic have lifted the Scottish Premiership title 14 times. European qualification every season with some elements of the top table to delight. Quadruple Trebles. A balance sheet with cash reserves the envy of most much larger fish in a European context. The trophy cabinet overflows. The stadium is frequently sold out. So why the discontent?

Step back, take a breath, add some context and have a look at the map of European football’s light to middleweights—clubs from Norway’s Arctic Circle, from the Danish heartlands, from Belgium’s competitive cauldron—and a more uncomfortable truth emerges. Celtic have been culturally downsized. European ambitions, once embodied by a Lisbon final and latter‑day nights against Barcelona, Manchester United, Man City and Bayern Munich, have been recalibrated downward to a passive acceptance of participation over progress.

Celtic frankly are no longer structured for European growth. It’s arguable we never were. Meanwhile, the one point ahead of Rangers mentality has allowed the clubs competitors in comparable leagues to quietly build the machinery Celtic lack.

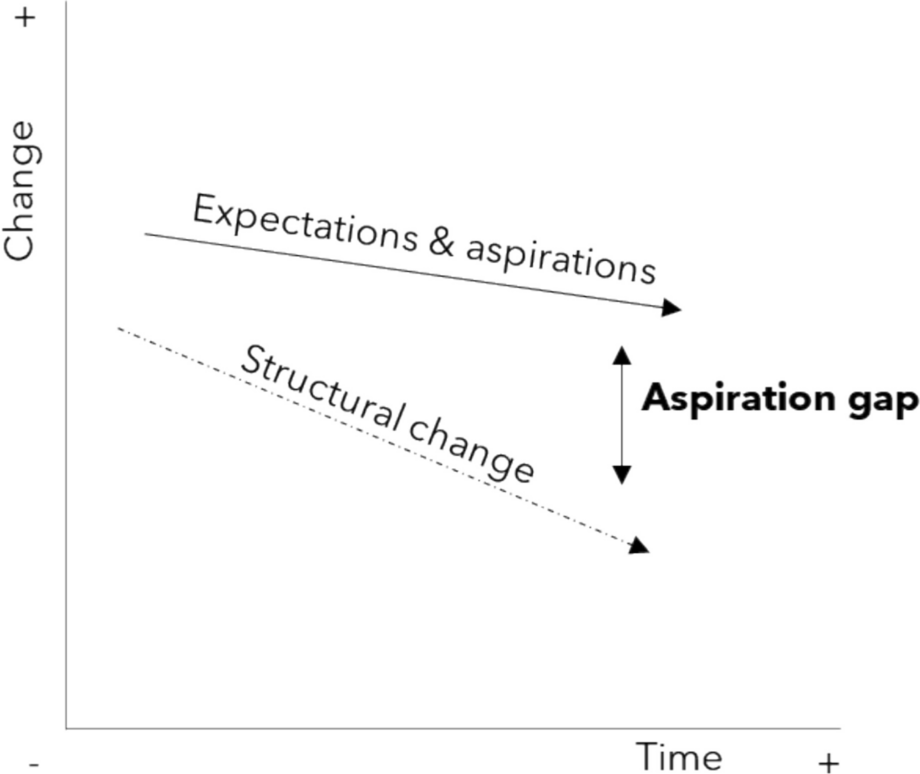

THE ASPIRATION GAP—WHEN PARTICIPATION REPLACES PROGRESS

Celtic are no longer judged by the standards of Europe’s elite. We’ve known that for a while now as we evolve to a “bucket list” destination for European teams and players. The evidence clear now is even more damning; we have also stopped being judged by the standards of Europe’s overachievers.

Champions League group stage participation has become an exercise in damage limitation. Since 2013-14, Celtic have won just five of 34 group stage matches. We have progressed to the knockout rounds once in the past 17 years. The Invincible Treble season of 2016-17, when domestic perfection was achieved, yielded zero Champions League points.

This is the aspiration gap. Domestically, we measure ourselves against Rangers and the chasing pack. European success is defined by “competitive performances” and “learning experiences”—the language of the plucky underdog, not the serial champion.

Contrast this with Bodo/Glimt. A club from a town of 50,000 people, 16 hours north of Oslo, playing in a stadium that holds 8,200 spectators . Their wage bill is a fraction of Celtic. Their recruitment budget in 2017 was €4.2 million. And yet, in April 2025, they stood in the Europa League semi-finals against Tottenham Hotspur. In August 2025, they became the northernmost club in Champions League history . They have beaten Roma 6-1. They have eliminated Celtic. They are on the cusp of defeating Inter Milan.

“We don’t believe in miracles, we believe in our journey,” : Kjetil Knutsen after eliminating Lazio. That journey has produced four league titles in five years—but more importantly, it has produced a European identity. Bodo/Glimt do not enter continental competition hoping to avoid embarrassment. They enter expecting to progress.

Or consider FC Midtjylland. A club that did not exist until 1999—formed from a merger of local rivals—topped the same Europa League table we muddled our way out of thanks to MON. The dismantled us 3-1 at the MCH Arena . Their wage bill is one‑third of ours . Their stadium capacity is smaller than Kilmarnock’s. Yet their “Vision 2025” project, launched from 112th in the UEFA rankings, aimed for the top 50. They currently sit 64th.

The Danish club’s ambition is written on the walls of their training base. Literally. The word “Dream” greets visitors, alongside a stated goal to produce both a Ballon d’Or winner and a Prime Minister.

And then there is Club Brugge. The Belgian champions operate in a domestic league with genuine competitive depth—Anderlecht, Genk, Union Saint-Gilloise, Antwerp all challenge annually. Yet Brugge have built something Celtic lack: structural patience.

In January 2026, Club Brugge rejected cumulative transfer offers exceeding €100 million for three players—Raphaël Onyedika, Joel Ordóñez and Christos Tzolis . CEO Bob Madou explained the rationale with devastating simplicity: “It’s simple: if we keep our best players, our chances of winning the league are greater. And that brings income—via the Champions League and added value on transfers” .

This is the fundamental cultural shift Celtic have failed to make. Brugge understand that squad stability drives European qualification, which drives revenue, which drives future transfer value. Celtic understand that selling players generates profit. They have not yet connected the dots to show that retaining players at the right moments generates more.

Compare that to World Class Basics.

THE FINANCIAL PARADOX—MORE MONEY, LESS IMPACT

The irony is as laid out in the tagline. The richer we’ve become the more we’ve declined.

Celtic’s revenue consistently exceeds that of Bodo/Glimt, Midtjylland and Club Brugge individually. We generate matchday income from 60,000 spectators that most European clubs can only imagine. Commercial operations benefit from a global supporter base that Midtjylland, with respect, could never replicate.

And yet the return on this financial advantage, measured in European progress, is negligible.

The comparison with Midtjylland is particularly instructive. The Danish club’s transfer spend rose from €3 million in 2016-17 to €36 million in 2023-24 . That growth came from steady player trading—buying smart, developing systematically, selling at peak value, reinvesting strategically. It is the Brentford model, transplanted to Jutland, because Matthew Benham understood something that Scottish football has been slow to grasp: analytics-based recruitment is not a marginal gain, it is the central plank of sustainable overachievement.

Midtjylland had a set-piece coach before set-piece coaches were fashionable. They have been doing it for over a decade. Previous incumbents now work at Aston Villa, Newcastle United and the German national team . When the Premier League and four‑time world champions recruit from your staff, you are doing something right.

What is Celtic’s equivalent innovation? Where is the department head that German or English football poaches?

The financial paradox deepens when examining the AGM dynamics. In November 2025, shareholders proposed resolutions for a three-to-five year strategic plan and board restructuring. They were defeated by margins exceeding 98%, thanks to a controlling shareholder bloc that protects the establishment from external challenge . The Celtic Trust’s attempts to secure accountability were met with procedural obstruction and public statements blaming “organised disorder” .

This is not the governance structure of a club preparing for European growth. It is the governance structure of a club defending a status quo that ultimately will lead to its demise.

PATHWAYS—OUTPUT WITHOUT THROUGHPUT

If there is one area where Celtic should dominate their peer group, it is youth development. The catchment area, the scouting network, the prestige of the jersey—all should combine to produce a conveyor belt of first-team talent and saleable assets.

The reality is sobering.

Over the past decade, Celtic have produced four consistent first-team regulars from their academy: Callum McGregor, James Forrest and Anthony Ralston and Kieran Tierney. Tierney is the perfect example of the player trading and generating model we espouse but…hundreds of others have passed through the system. Most depart quietly, for nominal fees, to careers in the Scottish Championship or minor European leagues.

The roll call of departed talent is painful reading. Karamoko Dembélé, once a viral sensation at 16, left for Brest on a free transfer. Liam Morrison joined Bayern Munich without playing a senior game for Celtic. Ben Doak, whose explosive debut at 16 suggested a generational talent, was sold to Liverpool for a modest fee months later . Mitchell Frame, a Champions League debutant against Feyenoord, transferred to Aberdeen in 2025.

The pattern is consistent: early promise, limited exposure, quiet exit. Utter waste.

Contrast this with Bodo/Glimt’s approach. Patrick Berg, the club’s captain and midfield heartbeat, returned home after a spell at Lens because the project mattered more than the pay cheque. Ulrik Saltnes has spent his entire career at the club. Jens Petter Hauge left for AC Milan and Eintracht Frankfurt, then returned. This is not sentimentality—it is structural commitment to a playing identity that transcends individual personnel.

Bodo/Glimt’s revenue reached €60 million last year, up from €4.2 million in 2017. That growth came from European prize money and player sales—but crucially, it came from keeping the squad together between sales. They sell at the right moment, not the first moment. They reinvest in the academy, not just the first team. See Maeda, Daizen and Engels, Arne for reference.

Red Bull offers another reference point. Salzburg and Leipzig operate a multi-club structure that develops players through controlled environments, maximising both performance and transfer value. Players move from FC Liefering to Salzburg to Leipzig, gaining European exposure at each stage, before being sold at peak market value. By contrast we punt and hope. See Balde, Amido and Yamada, Shin and fcuk knows how many others for reference.

Celtic cannot replicate the Red Bull network overnight, nor flick a switch into cultural solidity like Bodo. But the principle—structured progression, clear pathways, patient monetisation—is entirely transferable.

Celtic’s academy should be a launchpad. Too often, it has been a revolving door or a wasteground for talent. Fixing that will take some time.

So how do we break through? What can we do, even with the current idiocy in charge?

On the evidence of Bodo/Glimt, Midtjylland and Club Brugge, a five-year roadmap to Champions League competitiveness isn’t pie in the sky.

It just requires different toolsets to an overpaid lawyer and beancounter in Nicholson and McKay.

A different model from the ‘identify good young players coupled with automatic Champions League qualification’. The latter is now beyond of us because of the coefficient.

Is there a Virgil or a Khun among our recent signings? BTW I don’t think you mentioned Tierney from our academy.

Can the supporters be more helpful than embarrassing the club all over Europe and incur more EUFA fines, really not clever. The Board is going to change over the Summer, will the new Board possess more imagination than the current mob.

A brilliant article which really hits home. I often use the Bodo Glimpt example when countering those who go on about financial disparity etc. As we all know, the Board is full of yes men, the CEO, a company secretary temporarily promoted by Lawwell and told to keep his nose clean. NOTHING will change until Desmond goes whether that is through a buy out or shareholders coming together to match his shareholding ( Celtic Supporters Ltd approach) I fear for us now as the Huns appear to have their act together with strong financial backers

Agree 100%, this team is in freefall due to the board. Last nights football was horrific, no passion, no heart, they looked like a team that had met 5 minutes before kick-off. We really need to spend lots of millions on players that slot right into the team, not young ” for the future players ” that 90% of the time don’t make the grade. We really do need a take over from Desmond,and a clear out of the inept board, that are truly holding Celtic back. HH

Magnificent piece. Magnificent.